Disabled Design History & Rights: 101

Written & created by: Alexa Vaughn

A number of events led us to where we are today, to the rights the disabled community has gained. I believe access to public space is a civil right, not a privilege. But today, disabled people’s very rights to exist and to use public space are still being questioned. If we continue to choose to exclude disabled people in our designs (both process and product), we continue to commit a serious injustice towards these people.

The Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s-70s took place in large part at my alma mater, UC Berkeley. But the disabled community’s rich, parallel history is often forgotten and erased. The Disability Rights movement was spearheaded by disabled people and the community continues to fight for our rights to public space. This movement is still very much alive – it is not past, but present.

Image Description: A black and white photo of a protest that took place at UC Berkeley in the 1970s There are disabled protestors chanting and holding protest signs. A large sign to the right stands out and reads (in handwriting): Every Body Needs Equal Access.

In the early 1970s, Professor Emeritus Raymond Lifchez led a studio course at UC Berkeley with Barbara Winslow, which brought physically disabled people into the classroom, as stakeholders and experts, to provide guidance and feedback to non-disabled students’ architecture projects. This is not common practice today in the classroom nor in our profession.

Image Description: A black and white photo of a university architecture studio at Wurster Hall (now Bauer-Wurster Hall), UC Berkeley, in 1972. Non-disabled architecture students sit around a table that has cardboard architecture models, with physically disabled stakeholders giving feedback. In the background are studio desks, large pieces of paper, and other architecture models.

Section 504 of the Federal Rehabilitation Act was signed into law in 1973, which would prohibit exclusion of or discrimination against disabled people under any program or building receiving federal funding. However, in 1977, four years later, it had yet to be implemented. In April of 1977, demonstrations led by the disabled community began across the United States. Judy Heumann and Kitty Cone led the largest non-violent occupation of a federal building in US history in San Francisco, where over 100 disabled protestors and their allies, such as the Black Panther Party, occupied a federal building for just under a month. They got Section 504 implemented as a result, through collective and intersectional protest, and these regulations would lay the groundwork for the more comprehensive Americans with Disabilities Act, 13 years later.

Image Description: A black and white photo of the Section 504 protest in 1977, inside a federal building in San Francisco. The room is full of disabled activists with a diversity of cultural backgrounds, many in wheelchairs. In the middle is a white woman signing in ASL and to the right is a man standing with a video camera.

Most of us are familiar with the Americans with Disabilities Act passed in 1990, but similarly to Section 504’s history, the disabled community’s extensive efforts are often forgotten and erased. In 1990, disabled people marched on Washington D.C. to spur congress to pass the ADA. To illustrate their struggles with inaccessibility to the built environment, physically disabled people took to the Capitol building steps and crawled their way up. The ADA was passed on July 26, 1990 and directly influences our legally-binding accessibility standards.

Image Description: An image (in color) of the Capitol Crawl in 1990, in which physically disabled protestors crawled up the Capitol Steps in D.C. to push for the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Most of the protestors wear blue t-shirts and crawl backwards up the stairs, sitting on their bottom. A few crawl forwards on all fours. Carers and assistants help to transfer some folks out of their wheelchairs at the front, bottom of steps.

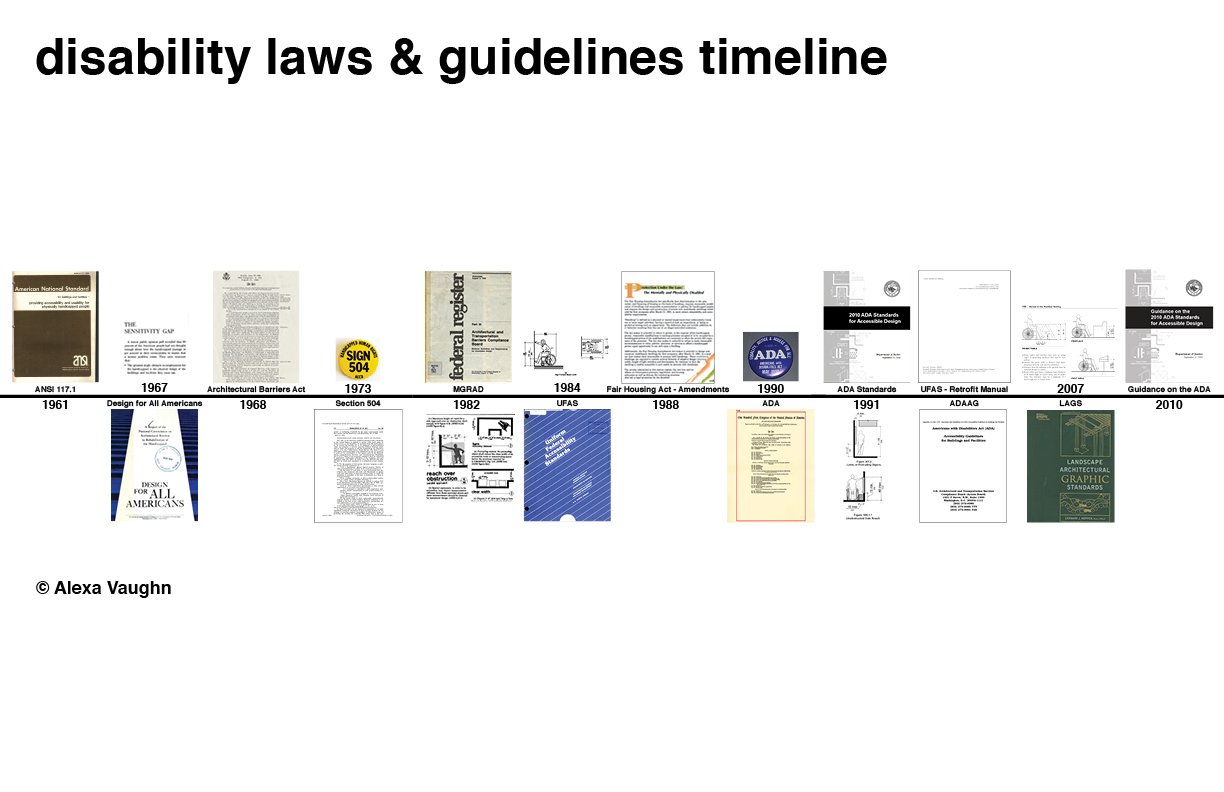

Image description: A timeline, made by Alexa, of a selection of disability rights laws and guidelines. It begins at 1961 with ANSI 117.1, Design for All Americans in 1967, Architectural Barriers Act (ABA) in 1968, Section 504 in 1973, MGRAD in 1982, UFAS in 1984, Fair Housing Act Amendments in 1988, ADA in 1990, ADA Standards for Accessible Design in 1991, UFAS Retrofit Manual and ADAAG, the Landscape Architectural Graphic Standards in 2007, and Guidance on the ADA in 2010. Each of these includes a small image of the cover of the standards or snapshot of the law. Some include buttons (“Sign 504” yellow button, blue ADA button). And some also include a snapshot of what the graphics look like.

Image description: The black and white cover of the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. The left side is a gray bar, and examples of some of the graphics in the book are overlaid on the gray bar and the white background. The title is in white text over a large black bar at the center. In the upper right corner is the seal of the Department of Justice.

The ADA Standards for Accessible Design, our design “bible” for access, was published in 1991, a year after the passage of the ADA, and its most recent version was released 11 years ago, in 2010. Many states have their own codes, but all must comply to the ADA Standards as baseline. Despite its age, the ADA Standards are treated as a catchall for any site accessibility needs throughout the country. Despite their shortcomings, the Standards are a direct result of the disabled community’s fight for civil rights to access public space.

As an extension of this selection of laws and standards, Ronald Mace created the seven Universal Design principles with the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University in 1997. These principles are not legally binding, but the fact that Ronald Mace was a disabled architect, consultant, and professor - in other words, a disabled expert! - make them very unique.

I believe Universal Design principles have the power to serve as a creative tool alongside our legally-binding standards. There is power in their flexibility and adaptivity. We can continue to shape the legacy of the Disability Rights Movement by going beyond the bare minimums that have been achieved, legally, in this country. We can put our whole creative heart and soul into our work and become true allies to the disabled community, driven by action. We can consciously choose to create a more accessible and inclusive world.

Written & created by: Alexa Vaughn

Disclaimer: This is not meant to serve as legal advice, nor serve as a substitute for access laws or requirements. These opinions are my own, as a disabled / Deaf person, and not necessarily those of my employer. Please consult the ADA Standards and other applicable state and federal codes for legal accessibility requirements for each project you pursue. This is meant to serve as a creative tool to be used as a supplement to any / all legal requirements, which must be met as bare minimum, before branching out to Universal Design principles and direct disabled stakeholder and expert feedback.