How to Talk To & About Disabled People in the Design Process

Written & created by: Alexa Vaughn

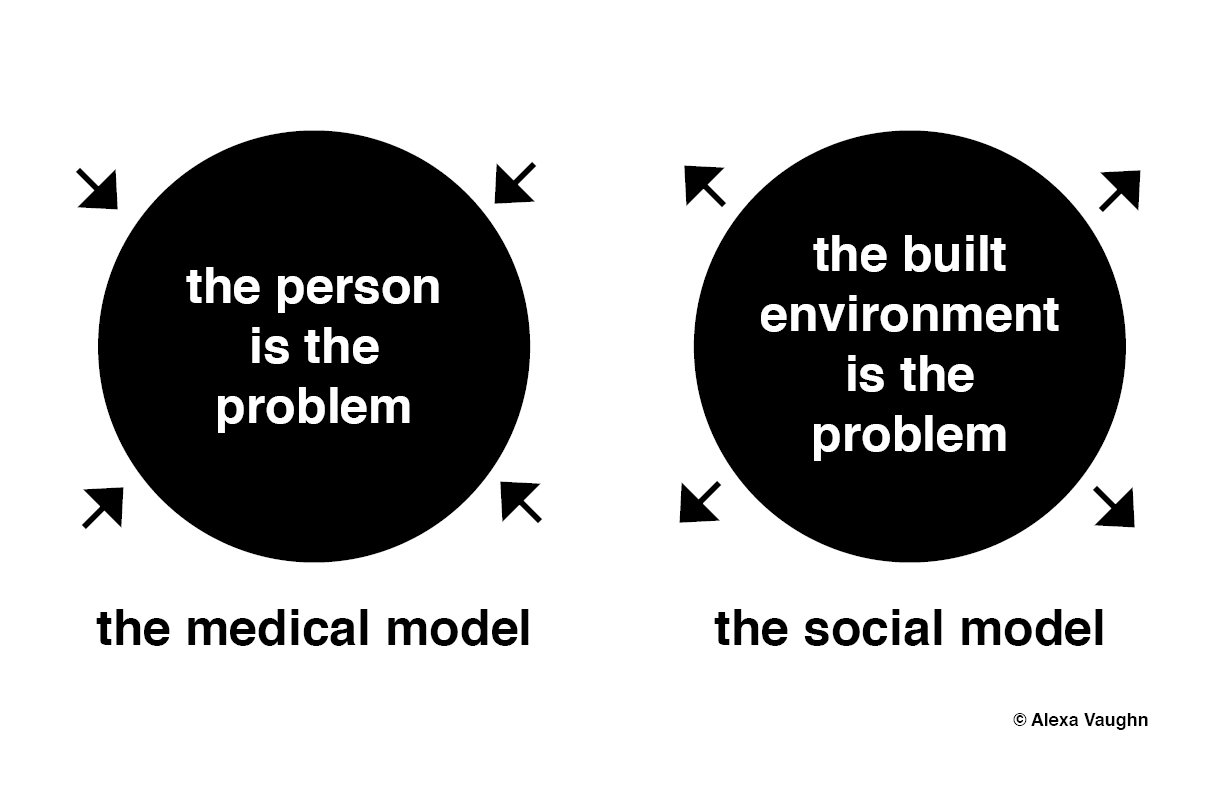

Language Matters: The Medical Model vs Social Model Worldview

Image description: A simple black and white diagram graphic, illustrating the medical model vs. the social model. To the left is the medical model, it is illustrated with a black circle with white text within that reads “the person is the problem;” four arrows face towards the circle. This emphasizes that the medical model treats individually-held disabilities as issues to be solved. To the right is the social model, it is illustrated with a black circle with white text within that reads “the built environment is the problem;” four arrows face outwards away from the circle. This emphasizes that the social model treats the built environment as an external issue to be solved.

A paradigm is a typical example or model that the world follows, by majority. Did you know that we have a paradigmatic worldview about disability and the built environment?

The medical model is the dominant worldview of the built environment. It views disabled people as the problem, and as a result, disabled people are constantly forced to adapt themselves to the built environment. If a disabled person is not able to “fit” into or use a space, the pressure is on them to figure it out or to otherwise “fix” themselves. Oftentimes, nondisabled designers limit their thinking of disabled people’s use of space to healthcare, medical centers, or therapeutic spaces, not the broader, public realm. Why is this problematic?

In stark contrast to the medical model worldview, the social model of disability views the built environment as the problem. As landscape architects (and related professionals), we need to adopt a social model worldview. Disabled people should not be forced to adapt themselves to our designs and we must begin to view disabled people as human beings, deserving of spaces not only to access (at a bare minimum) but to thrive in and enjoy, beyond medical spaces. There are over 1 billion disabled people worldwide, many using public spaces every day. This is roughly 1 out of 7 people globally and 1 out of 4-5 people in the United States with some type of disability! If we are designing inaccessible public spaces, many, many people are being affected. We need to fix and “cure” the built environment, not the people who use it.

To read more about the Medical vs Social Models, read: Enabling Justice: Spatializing Disability in the Built Environment by Dr. Victor Pineda.

Image Description: A black and white diagram graphic, with black and white vector symbols representing physical disability, deaf and blindness, and neurocognitive disabilities, illustrating disability as a spectrum. Underneath the symbol of the wheelchair for physical disabilities reads a list: paraplegia, quadriplegia, spinal cord injury, spina bifida, cerebral palsy, cystic fibrosis, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, dwarfism, amputees, ehlers danlos syndrome, diabetes, & more. Underneath the sensory symbols of crossed out ear and crossed out eye read: deaf, hard of hearing, late-deafened, blind, low vision, deafblind, anosmia, aguesmia, & more. To the right, under the neurocognitive symbol of silhouette of a head with question marks inside read: autism, a.d.d., a.d.h.d., dyslexia, down syndrome, dementia, alzheimers, learning disabilities, psychological disabilities, & more. (This list is not a complete list).

Disability is a very broad spectrum, ranging from physical (and mobility) to sensory, to neurocognitive and mental disabilities. Many folks identify with more than one disability across this spectrum. Many of these disabilities are what we call “invisible” – some disabled people use wheelchairs, some use other assistive devices like tactile canes, hearing aids, glasses, or prosthetics; but others use no (or invisible) assistive devices, so disability is not always visible or easily identifiable. The disabled community is actually the most diverse and intersectional minority group, globally and it is a community that anyone might join at any time.

Despite this, there is a false belief in society that disabled people are confined by their disabilities and spend most of their time in medical spaces, not the public realm. Due to the fact that these misunderstandings exist and non-disabled people tend to pity disabled people - thinking that they suffer in medical institutions - there is a discomfort in talking about disabilities and including the disabled community in the design process. We must begin to take a more holistic and richer approach to the disabled community and to account for diversity and variance in our designs as much as possible. We can no longer assume that only one type of disabled person is using a space at a given time.

So, why is the language we use in the design process, to talk about (and to) the disabled community, important?

You may have noticed by now that I use the term “disabled people” to describe folks identifying in some way with a disability and with the broader disabled community. As a Deaf woman myself, I choose to use identity-first language to describe people who identify with any type of disability. This can also vary between certain identities; for example: Deaf or hard-of-hearing person, Blind or low-vision person, physically disabled person, Autistic or neurodivergent person, and so on. Many folks can identify with one or more of these disabilities (always remember, disability is a spectrum!).

Part of the reason I use what is called identity-first language is because disabled identity is very important to me and to other disabled community members. I came into a sense of pride as a Deaf person (and member of the broader disabled community), and before taking on that identity, I held a lot of internalized ableism against myself. This internalized ableism came directly from the medical field and society at large: a world that viewed me as “impaired” and in need of fixing or a cure for my “hearing loss.” So, it comes as no surprise that I hid my disability from non-disabled people for the bulk of my life, until claiming it and changing my perspective from the medical model to the social model. Another part of my reasoning is that almost every other cultural identity puts identity first. For example: Black woman, Muslim man, queer person. You would not necessarily say “a woman who is Black,” “a man with Islamic faith,” or “a person who is queer.” It’s just awkward!

It must be noted that it takes time for many disabled folks to become comfortable with identifying as disabled, and furthermore, empowered by their identity. Some folks never become comfortable identifying as disabled, but this is completely OK and a personal choice. The United States and the United Nations still predominantly use what is known as person-first language, which describes disabled people as “people with disabilities” or “persons with disabilities.” This is completely acceptable and officially recognized terminology, and preferred by some members of the disabled community. The strongest (and most positive) argument for using person-first language is that it asserts the person’s humanity, first, and places disability as only one part of that person’s identity.

However, we should refrain from describing disabilities as impairments, disorders, or losses, which can carry negative medical-model connotations. For example, this includes: a hearing impaired woman, child with Autism Spectrum Disorder, or person confined to a wheelchair. Personally, as someone who identifies as Deaf / disabled, I find person-first language, when not used at its best, to have some cons: it can be used to downplay disabilities to make non-disabled people more comfortable, it can perpetuate ableism and internalized ableism, and it can also be very medical in nature. For example, as I mentioned earlier, I used to identify as a “person with hearing loss” and people would describe me as “hearing impaired” or a “person with a hearing impairment.” In this case, person-first language can fall short - although it tries to frame humanity - by highlighting what the medical field and society at large deem to be a disorder or something that is “wrong” with a person, to frame a loss. This negatively insinuates that disabled folks deserve pity and live lives that lack capacity for joy, which simply isn’t true. So these are all important things to keep in mind.

If this seems tricky and you are not sure how to refer to someone: the most important thing to do is to simply (and always!) ask what the person prefers. This is similar to asking for a person’s pronouns (for example: she, he, they, ze, xe). It is a learning process and varies person to person. This entire section is regarding my personal preferences, which do not reflect those of the disabled community as a whole. Personally, I do not see disability as something to be ashamed of - disabled is not a bad word.

Identity-First Language:

Disabled People*

commonly used in the United Kingdom and European countries and by self-identifying members of the global disabled community

Person-First Language:

People with Disabilities (PWD)

commonly used in the United States, sometimes interchangeably

Persons with Disabilities (PWD)

commonly used by the United Nations

* Identity-First is Alexa’s preference

Additional Note

Crip, Mad, and Beyond: Reclaiming Derogatory Language about Disability

Throughout this website and in everyday references to the disabled community, I use identity-first language to describe disabled people and their unique identities. I feel that claiming disabled identity is empowering and a source of pride, which is particularly true for the Deaf community. It is worth noting here that we should avoid using outdated, derogatory language to describe disabled people. This language goes beyond medical model terminology into completely unacceptable language that is meant to harm. For example, we should not use terms such as: crippled, handicapped, handi-capable, deaf and dumb, or the ‘R’ word when describing disabled people.

Some disabled folks have reclaimed derogatory language and made it their own, with a true sense of pride in identity, particularly with the term Crip, used by physically disabled people (for example: Crip the Vote, Crip Elder); and Mad, used by mentally disabled, mentally ill, and some neurodivergent people (for example: Mad Pride). Unless these folks give you permission to use this language, we should assume it is reserved for their use, and within their community, only.

Written & created by: Alexa Vaughn

Disclaimer: This is not meant to serve as legal advice, nor serve as a substitute for access laws or requirements. These opinions are my own, as a disabled / Deaf person, and not necessarily those of my employer. Please consult the ADA Standards and other applicable state and federal codes for legal accessibility requirements for each project you pursue. This is meant to serve as a creative tool to be used as a supplement to any / all legal requirements, which must be met as bare minimum, before branching out to Universal Design principles and direct disabled stakeholder and expert feedback.